After the euphoria of the Paris climate negotiations last year, a more mundane but significantly important set of negotiations are underway, which will shape the design of our homes, the growth of our industries and the future of the planet.

After the euphoria of the Paris climate negotiations last year, a more mundane but significantly important set of negotiations are underway, which will shape the design of our homes, the growth of our industries and the future of the planet.

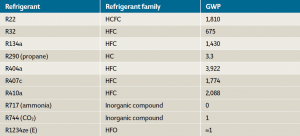

Policymakers from across the world met recently in Vienna under the aegis of the Montreal Protocol to agree to a phase down pathway for hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). HFCs are potent greenhouse gases, largely used as refrigerants in refrigerators and air-conditioning for homes, commercial buildings and vehicles, but with global warming potential of thousands of times as compared to carbon dioxide.

An amendment for limiting existing and future production and consumption of HFCs has been described as the most significant step for mitigating climate change after the Paris Agreement. The Vienna meeting showed that the world can move forward on this important issue, but also that there are still some key differences that remain between countries.

Positions of various countries

There are four amendment proposals on the table: from the European Union, India, North America, and the Small Island States. All the four proposals are fairly similar in terms of the efforts for phasing down HFC consumption in non-Article 5 parties (developed countries). For Article 5 parties (developing countries), however, the Indian proposal differs significantly with a higher baseline (2028-30 relative to a historical baseline) and a later freeze date (2031 relative to 2020-21) for HFC consumption and production.

There are agreements on some issues like financing, but there is a clear lack of agreement on baseline and freeze year. Within the Article 5 grouping, China and African countries seem to agree with an earlier freeze, Middle Eastern countries seem to be comfortable with a date around 2025, while India has stuck to its stated position.

Arguments for an early phase down

The most important rationale for an early baseline and freeze year is mitigation of potential HFC emissions and the resultant decline in global warming. A later baseline, as in the Indian proposal, will lead to higher cumulative emissions from Article 5 parties. The second most important reason is a strong policy signal to the market.

Developed countries argue that with the policy signal of early freeze date, technologies will evolve and mature by the required time for developing countries. For example, the North American proposal gives a five-year grace period to developing countries for freezing HFC production and consumption, and experts argue that this period is sufficient for technologies with low global warming potential (GWP) to emerge for different sectors, because developed countries would have already begun their transition earlier. Along with the grace period, all the proposals also give flexibility to countries to choose which sectors should transform earlier and which later.

Indian position

While the argument on environmental impact of a later baseline and freeze is a valid argument, there is disagreement on timely availability of technologies. India has highlighted that its prime concern is timely availability of unpatented and cost-effective low GWP refrigerants. It argues that the grace period of five years might not be sufficient to address this concern.

This concern essentially reflects the uncertainty associated with the availability of unpatented, technically effective, and cost-effective technologies for the key large HFC using sectors. Accepting an early freeze could potentially lead to serious challenges for production and consumption sectors in India, which are growing at a rapid pace – and would impact manufacturing and market access.

Transition costs

Research undertaken by the New Delhi-based Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) on modelling future HFC use and emissions has shown that the three major sectors will be residential air-conditioning (RAC), commercial air-conditioning (CAC), and mobile air-conditioning (MAC). CEEW’s analysis on cost of transition across sectors between 2015 and 2050 shows that given the current understanding of cost and efficiency of existing low-GWP alternatives, the transition cost would be EUR 12 billion (INR 894.2 billion or USD 13.4 billion) for the Indian proposals, and EUR 32-34 billion for all the other proposals, mainly in the MAC sector.

At the same time, there is a huge opportunity in terms of savings through energy efficiency, to the tune of EUR 49 billion for the Indian proposal and EUR 53-54 billion for the other proposals, mainly in the RAC and CAC sectors. These numbers are not set in stone, and will change with changes in refrigerant costs and efficiency.

It is important to understand what needs to be done for minimising cost and maximising the efficiency gains. Currently, there is no concrete understanding of the potential future trajectory of refrigerant price for the low-GWP alternative for the MAC sector. Future prices critically depend on the potential to derive monopoly rents as well as the refrigerant chemistry itself.

Technical experts need to sit together to get a better understanding of how low refrigerant prices can go in the next 20 years or so for the MAC sector depending on various factors. In addition, there is a crucial need for R&D in India for overcoming the technical barriers for alternative refrigerant in the RAC and CAC sectors, so that the huge opportunity can be harnessed. Many Indian industry representatives currently question the safety aspects of some key alternatives. These concerns, while important, can only be addressed through strategic R&D.

Need for differentiation?

Significant differences exist within the Article 5 (developing countries) grouping. African nations are expected to enter the high growth phase only after 25 years or so. Growth in China is already showing signs of tempering. India, however, is already in the initial stages of a high growth phase. Uncertainties around the cost and technical feasibility of refrigerants need to be viewed within the context of these differences.

It is important to emphasise that India is different from all other parties in the sense that it is expected to grow significantly in the next 25 years, and this growth could be impacted under an earlier phase-down if the potential challenges are not addressed. Development concerns are paramount for India. An early phase-down is possible only if it is aligned with the development concerns for the country.

To address the development concerns and uncertainties around cost and feasibility of low-GWP alternatives, developed countries might need to think about creating a framework that allows an ambitious phase-down while giving the rope to India for a later phase-down. In other words, creating differentiation among Article 5 parties to address their respective priorities and capabilities could be a way forward.

Source: http://indiaclimatedialogue.net/2016/08/01/hurdles-remain-global-clampdown-hazardous-refrigerants/