Paul Hawken, the editor of Drawdown, says that air conditioning contributes a shockingly high amount of atmospheric emissions. The global demand for AC is increasing rapidly thanks to rising economic prosperity in developing countries and higher average temperatures. By 2050, Hawken says hydroflourocarbons, the refrigerants that make air conditioning possible, will account for 19% of all atmospheric emissions. If the world got 21% of its electricity from wind turbines by 2050, the carbon emissions saved would be exceeded by the carbon emissions created to keep us all cool. The world may be going to Hell in a handbasket, but at least we will be comfortable on our journey to purgatory.

Paul Hawken, the editor of Drawdown, says that air conditioning contributes a shockingly high amount of atmospheric emissions. The global demand for AC is increasing rapidly thanks to rising economic prosperity in developing countries and higher average temperatures. By 2050, Hawken says hydroflourocarbons, the refrigerants that make air conditioning possible, will account for 19% of all atmospheric emissions. If the world got 21% of its electricity from wind turbines by 2050, the carbon emissions saved would be exceeded by the carbon emissions created to keep us all cool. The world may be going to Hell in a handbasket, but at least we will be comfortable on our journey to purgatory.

Scientists at the National University of Singapore report they have discovered a new way to cool air to as low as 65 degrees Fahrenheit without using any chemical refrigerants or compressors. How important a discovery is this? Hawken says if we could eliminate emissions from air conditioning, we could reduce the amount of average global warming by a full degree Fahrenheit (Assuming average global temperatures are set to rise about 5º F). To put that in perspective, that’s about the same as keeping all the emissions from all the diesel engines in the world out of the atmosphere.

Professor Ernest Chua says:

“For buildings located in the tropics, more than 40 per cent of the building’s energy consumption is attributed to air-conditioning. We expect this rate to increase dramatically, adding an extra punch to global warming. First invented by Willis Carrier in 1902, vapour compression air-conditioning is the most widely used air-conditioning technology today.

“This approach is very energy-intensive and environmentally harmful. In contrast, our novel membrane and water-based cooling technology is very eco-friendly — it can provide cool and dry air without using a compressor and chemical refrigerants. This is a new starting point for the next generation of air-conditioners, and our technology has immense potential to disrupt how air-conditioning has traditionally been provided.”

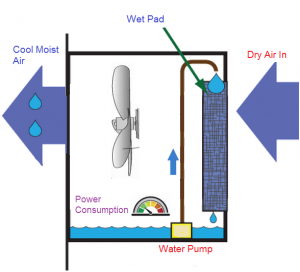

The key to the system is a paper-like membrane developed by the researchers. It removes moisture from incoming air, which is then cooled by a water-based dew point system. The result is cool air out and up to 15 liters a day of drinking water. The system uses 40% less energy than traditional air conditioning systems, which translates directly into lower carbon emissions if the electricity is provided by a fossil fuel generating station.

“Our cooling technology can be easily tailored for all types of weather conditions, from humid climate in the tropics to arid climate in the deserts,” Professor Chua explains.

“While it can be used for indoor living and commercial spaces, it can also be easily scaled up to provide air-conditioning for clusters of buildings in an energy efficient manner. This novel technology is also highly suitable for confined spaces such as bomb shelters or bunkers, where removing moisture from the air is critical for human comfort, as well as for sustainable operation of delicate equipment in areas such as field hospitals, armored personnel carriers, and operation decks of navy ships as well as aircraft.”

Work is continuing to make the new technology commercially viable and to integrate it with IOT sensors so it operates automatically without human intervention. If the system can be made cost competitive with traditional air conditioning equipment, it could alter the industry dramatically and make a significant contribution to lowering carbon dioxide levels in the earth’s atmosphere. This project is funded by the Singapore’s Building and Construction Authority and National Research Foundation.